Local literary translators talk about building the bridge from Quebec French to English

by J.B. Staniforth

The French spoken—and written—in Quebec has always been a flashpoint of discussion. Those who believe in the purity of the continental language policed by l’Académie Française impugn the French spoken here as vulgar and lazy. Others adore the local specificity of Quebec’s French, even seeing anglicismes (English words used in French) as enhancing rather than weakening the language. But as Quebec bears no resemblance to France, the French spoken here often shares little common ground with the “international” French that Anglophones are taught in school.

Bilingual people can tell their English friends about the complexity and magic of Quebec’s French, but those truly committed to sharing the language are those translating French works into English. For Sheila Fischman, an Order of Canada recipient and Knight of the Order of Quebec who is likely Quebec’s most prominent translator, translation began as an attempt to learn the language. She arrived in the Eastern Townships from southern Ontario in the late 1960s, and made her name with her 1970 translation of Roch Carrier’s 1968 novel La Guerre, Yes Sir!.

“When I first came to live in Quebec and didn’t speak French, someone suggested I try translating something,” she recalls. “I did that, but the first text that was suggested to me as a good place to start was a long story by Anne Hébert, called ‘Le Torrent.’ I couldn’t even understand it at that point. That didn’t work.”

Fischman eventually translated the Hébert story—and over 100 novels, including works by Michel Tremblay, Marie-Claire Blais, Roch Carrier, and Jacques Poulin.

“I like translating Quebec literature because it’s the books that I’ve read,” Fischman explains. “The stories I’ve read, and am still reading, have been my introduction to Quebec society.”

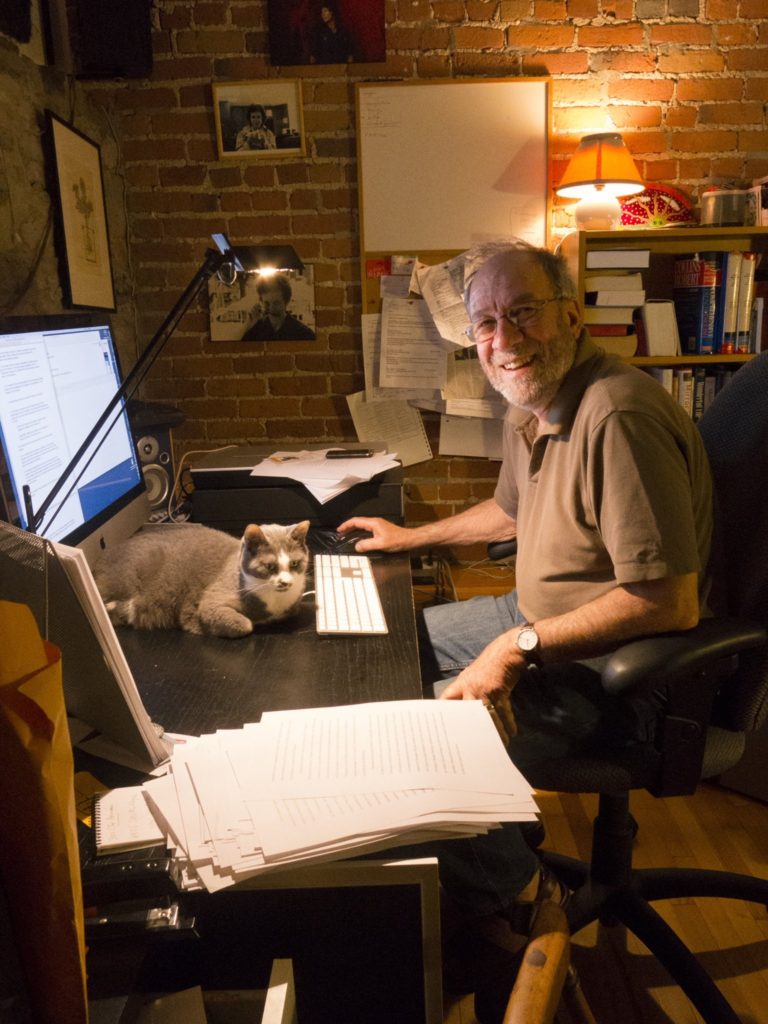

Documentarist and translator Donald Winkler is biased: he is Fischman’s husband. However, he notes Fischman’s bestselling translation of La Guerre, Yes Sir! was a watershed moment for Quebec French literature in English translation, coming at a time when English readers were anxious to learn as much as they could about “what Quebec wanted.”

Winkler became a translator in the 1980s after years of making documentaries about Canadian poets and authors.

“I used to tease some of my writer friends, saying ‘If you really want a Governor General’s Award you should switch to translation—the odds are better, sometimes there are only a dozen or so books submitted,” Winkler says. “That has changed big time. There’s a whole generation or more of younger translators doing fabulous work, a number of them writers in their own right. I think the opening up to more Indigenous, racialized, and LGBTQ books is operating in the world of translation, as everywhere else.”

Pablo Strauss is one of those younger translators: since translating Maxime Raymond Bock’s short story collection Atavisms in 2015, he has been nominated three times for the Governor General’s award. Strauss is passionate about choosing books for translation that resonate personally with him.

“The first story I read from the first book I translated, ‘Pastel Fear’ in Maxime Raymond Bock’s Atavisms, describes picking up mementoes on garbage day in Montreal, unearthing stories along the way. I saw pieces of myself and my friends in the stories,” Strauss recalls. “Whereas in my forthcoming translation, The Second Substance by Anne Lardeux, the characters’ experience may be far from my own—I’ve never been a mother, or a squatter—but I can relate to their struggle to find meaningful ways of living in a soul-crushing economic system. Like all the books I’ve translated, it has an honesty and urgency I want English-language readers to hear.”

Strauss bristles at questions about the thorniness of Quebec’s highly idiomatic French, noting to call a work “untranslatable” fundamentally misunderstands the project of translation.

“You can’t have an exact copy in another language,” Strauss says. “But a new, different book that’s true to the spirit of the original, conveys the same energy and tells the same story—that can be done.”

Like Fischman and Winkler, Strauss acknowledges the jokes, slang, and wordplay in Quebec French pose the greatest challenge.

“There’s no magic solution, you just examine every case closely—every sentence, every word—and try out five or twenty solutions till one sticks,” says Strauss. “Looking away from the original is important, having the confidence to let your translation live its own life, as a new work. For me, the process comes down to lots of drafts, usually around ten, and a good editor.”

Fischman concurs, noting: “You can’t always find an equivalent. You can try to make an equivalent. Any language has its peculiarities. Someone translating from English to French has comparable dilemmas.”

One of the most challenging aspects of Quebec French for Fischman is all the English. As a linguistic culture surrounded by English on all sides, vernacular French in Quebec has absorbed English in a variety of surprising ways—many of which are hard to translate. Fischman sees Anglicisms as having both enriched Quebec French and made it more challenging to translate.

“It’s tricky to work your way around and into a language that is influenced so much by the other, bigger language,” she says. “[With] one of my authors, as I was translating the work, it seemed as though it was half-English. The presence of English is a constant challenge.”

For Winkler, questions about the complexity of Quebec French often come down to oral, colloquial French often summarized as joual.

Those things are difficult, he notes, but “the prose in most Quebec books is perfectly straightforward.” Where the language becomes complicated for Winkler is in moments of geographical nuance.

“Books like those of Kevin Lambert, steeped in Saguenay regionalism, for example, require special attention,” he says. “But the author can be a lot of help in those instances.”

Fischman is perhaps best known for her many translations of Michel Tremblay, known for his vivid colloquialisms and joual.

“I guess Michel Tremblay’s novels present the biggest challenge,” she says. “Over the years, I’ve worked out a way of rewriting these novels in English in a way that doesn’t fool around with the French. [Tremblay] has been telling me with each translation that I’m ‘getting better and better.’ Which is very reassuring. I feel when something’s right. I can’t describe or explain that, but I just know.”

Having lived in Quebec more than fifty years, surrounded by Francophone friends and loving films in French, Fischman says the language has increasingly become a part of her.

“I surround myself with the French language, and eventually I become familiar enough that I feel I can paddle away in this language and come up with something that is honest and that works in English. How this happens, I couldn’t tell you. It’s a mystery.”

J.B. Staniforth is a Montreal writer and reporter.

Illustration by Nora Kelly

Read our earlier article about translated works from a publishing perspective.