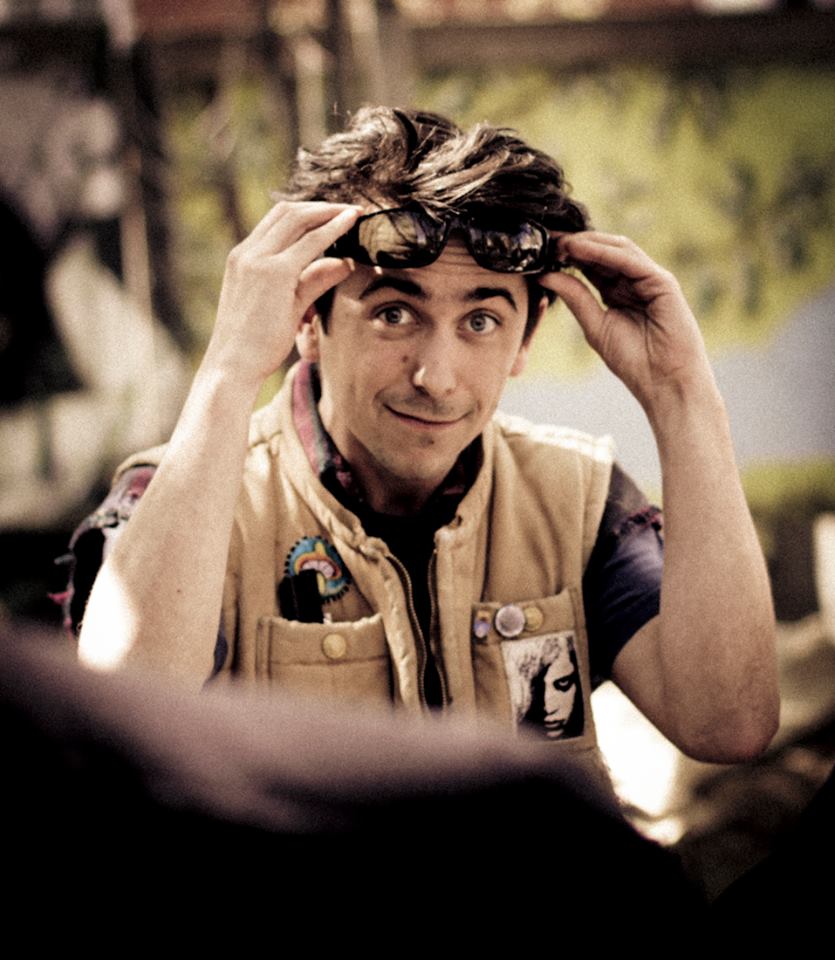

Multilingual children’s author, self-publisher and bookbinder Keenan Poloncsak on his process and inspirations.

by Esinam Beckley

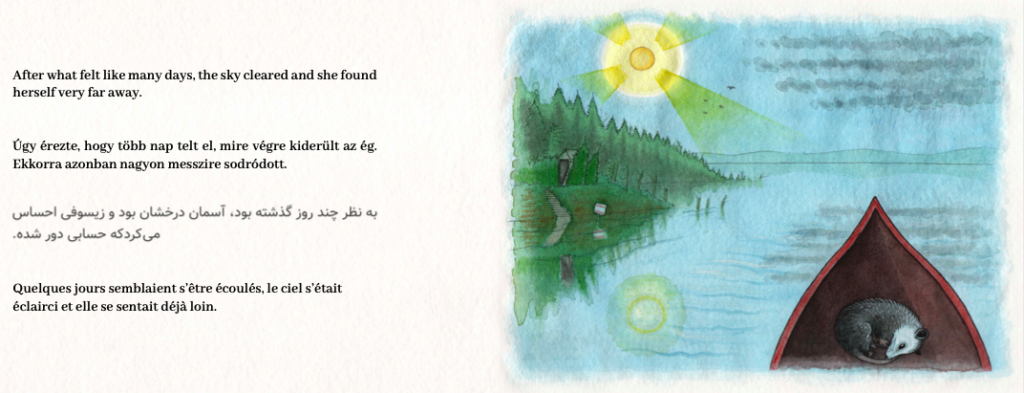

One afternoon, while leaving the Frontenac metro, just near the exit, I noticed someone selling books. This of course piqued my interest. The books being sold happened to be illustrated children’s books. It was on this day that I met Keenan Poloncsak. His previous book, Northern Mink, was trilingual – stumbling upon a trilingual children’s book was rare (and still is). His latest, Opossum’s Landing, is quadrilingual. A few of the themes and subjects explored in these works were gentrification, displacement, immigration, and alienation. (This was at a time before any of our current social movements were in effect.) These are the themes I personally find stand out the most, but everyone (adults included) can interpret these works of art in their own way. And they are truly works of art.

Poloncsak binds his own books, as well as repairs old volumes, at his shop, Le Relieur des Faubourgs (formerly The Bookbinder’s Daughter), in the heart of the East end of Montreal. The shop radiates the nostalgia of an old garment shop or/ factory: the walls are lined with various fabric and materials for books. It also holds workshops that teach the curious how to put together a book of their own.

Poloncsak inherited the shop from the previous owner Laura Shevchenko. He apprenticed for years with her, to learn the craft of book making. Before this, he was employed at a Montreal landmark site for artists, Papeterie St. Armand. Poloncsak’s journey is fascinating; I had to know more. So I sat down with this bibliophile and new father at his current shop in the East end. It was here Keenan regaled me with the tale of how it all came to be…

Esinam Beckley: What made you decide to create a multilingual children’s book?

Keenan Poloncsak: I had started with a simple story and so I wrote it in English. I thought “Oh, I should make it bilingual,” because I really speak both languages all the time. I’m more anglophone, but I speak French sometimes more than English in a day. I try to make things that I would like to read myself, too. I would have liked to have read bilingual books when I was younger, instead of just one language. It’s also more accessible. I thought, while I was at it since I want to reach more people, I might as well do a third language. I went for Spanish, because it’s a third common language, and I knew someone who could translate it.

For Northern Mink, I wanted to do the three languages of Quebec. I took a bit more time on it. Inuktitut is the Inuit language. It’s particularly the dialect of Northern Quebec. It’s not the dialect of Nunavut. Because there are four or five official dialects of Inuktitut in Northern Canada. The story is about a mink who lives up North in the Boreal forest. I like to fantasize too. At some point I thought “Oh, if I did it in Inuktitut, maybe I could go there and meet some people.” I called Kuujjuaq town hall. It’s a small town, and the mayor answered the phone. I told him I was looking for a translator, and asked if he knew anyone. He told me they did have a translator, but she was located in Montreal. So I was like, cool!

Then, for the new one Opossum’s Landing, that was my fourth book. So I thought I’ll do four languages (not that next time it will be five). It’s always English, French, and another different language. So, for the fourth time, I went with Hungarian, because those are my roots.

Hungarian is different, with lots of accents, but the alphabet is still Roman. For the fourth, I wanted something completely different. I chose Farsi, because I have a few Iranian friends. Farsi was interesting, because it’s a completely different alphabet. It’s also for people to learn. Someone from Hungary or Iran who is young can potentially learn a new language.

EB: There’s so much about displacement and trying to survive; what were you personally trying to include and get across with this book?

KP: I wanted to draw and write a book that children would like. I also wanted it to be aesthetically pleasing. Two main points for the kids are to entertain, and to inform. For example, opossums are actually a new species to Canada.

EB: Really? How new?

KP: It’s hard to say, but from what I researched, the government has officially recognized their existence on the territory of Quebec since 2000.

EB: That’s so recent!

KP: Very recent! But just like everything, just because the government has decided that now, does not mean they weren’t actually here previous to 2000. They’re from the States, they’ve been making their way up. I just find them to be super interesting as an animal. It’s an omnivore. It helps a lot of things in nature. Like nature’s garbage disposal, because they eat many things we don’t like. Like ticks. It eats a lot of ticks, but does not contract or give Lyme disease. Also it does not contract rabies. A lot of people see it as a big rat, and do not like it. But it’s a good animal. If you have one in your yard, you should be happy.

It came naturally to talk about a possum coming North that gets washed up in a flood in Quebec, and creates conflict. Immigration too, maybe, without saying the words. The opossum, she comes here, and people are like “Who are you? What are you doing?’’ same old shit. She has to deal with it, because she is stuck here. I also wanted to make it intense.

EB: Yes, I noticed death is one of the themes that are shown.

KP: Yes, I wanted to add a lot of true things to the story, without really mentioning it. The opossum gives birth, and the winter is really harsh. The part about getting frostbite on their ears is a real thing, because they are from the South. Or when she plays dead after she is attacked. They don’t live long, around two years. One technique of their survival is making a lot of babies. They are nomadic, they walk around, and the babies hang off of her. They are kind of like Johnny Appleseed, you know. They walk around and drop babies around. That’s their technique.

EB: I love that you included vultures.

KP: Yes, in the drawings there are vultures eating something, it’s gore but not. She is being told to go away by the lowest of the low. That is kind of what is going on in that picture. Vultures are considered an “undesirable,’’ so she is being told to go away by the bottom feeders.

EB: The aesthetics of the book are gorgeous. How did you decide which materials you would use or design to create it? It’s such a great shade of yellow, and physically, the book falls open beautifully.

KP: The material is very strong. It’s buckram, a standard high-volume usage material. It’s really made for kids, librairies, and schools in mind. It’s sewn, the paper is good quality. I have a stamping machine, so I tried so many colours. Yellow was really the colour that came out nice. Actually, the official colour of 2021 was also yellow.

EB: How would you like to see your books evolve, and what would you like to do eventually with your books?

KP: I rarely get offers. I’ve read my book in libraries and on stage to kids. But I never say ‘’Hey kids! This is about so and so.’’ I just hope they like it, and read the story. I really would like to do a reading somewhere, and I can read it in English and French. But I would like to have someone else to read it in all the languages. A big part of this is that I do not get a lot of breaks. It’s really hard work, and a little bit of good luck. Even with the shop, the stars were aligned. With Laura, I never at all thought she would pass it on to me. I just loved working with her, and in this field. It just so happened that this is what happened.

One thing I’m really trying to do is get Opossum’s Landing into libraries! Actually, the most libraries possible. Libraries and schools get special pricing if they contact me directly. I would rather this book be in every single library in the world, rather than one bookstore. The idea that a kid could stumble upon it, and like it. Bookstores never cut me any slack, and it’s almost like paddling upstream. I’m not against it, it’s just so complicated. No matter where you are, if people ask their local library to order a book, that’s the way to counter the system. If people ask, the library will buy it.

Find out more about Keenan’s work on his website. He will also appear in person at the Montreal Comic Arts Festival/Festival de BD on May 27 -29! The festival tents will be set up on Saint-Denis, between Gilford and Roy.

Esinam Beckley is a full-time scribe, student for life, and film enthusiast. She enjoys collecting the written word, tinkering with music wires in her bedroom, but especially mixing the two. She loves her parents, knitted garments, and art.

Illustration by Nora Kelly